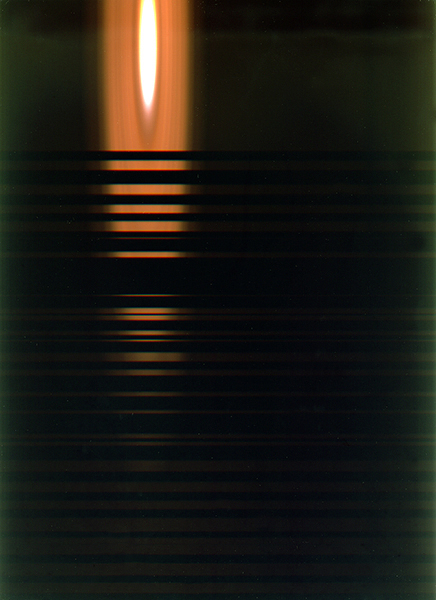

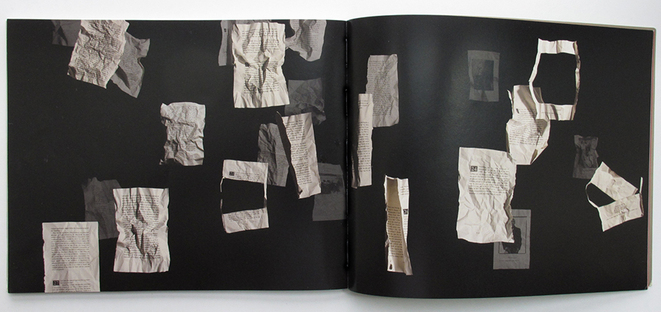

Digital image captured using a scanner and available light

|

VISUAL BLOG: I have decided to create a space where I can post miscellaneous images and ideas (things that are either in process or that are sitting in my "archive" and that for a variety of reasons hadn't been shared). For this first Visual Blog entry, I am sharing the beginnings of a project I called "A Sign of Our Times." A Sign of Our Times

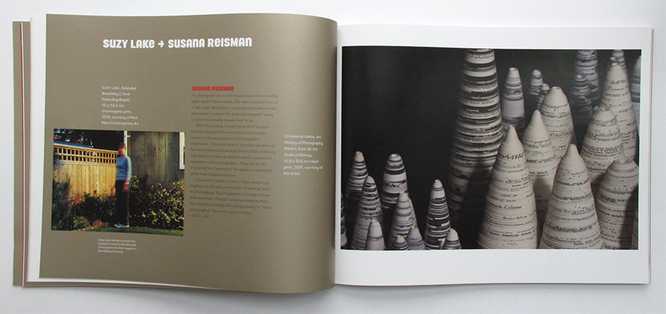

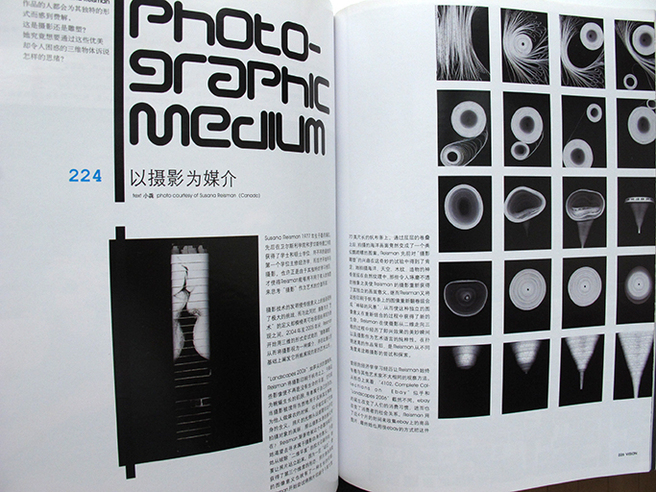

In March, 2010, Time Flies received a mention in the “Opera Prima” category of the prestigious BolognaRagazzi Awards at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy.  What the Jury Said: In Susana Reisman’s world, lines vibrate, triangles sing and numbers recall metaphysical clocks counting out the hours of eternity. Echoing Klee, Matisse and other 20th century artists, the artist aims to mesh music and painting. The result is so convincing that the pages seem to come alive. The tone, however, is always light-hearted, the medley of references and citations is always a source for enjoyment. The meticulous style provides an elegant framework for this delightful composition. Pictured: Author Susana Reisman (right) and publisher Nadine Touma (left) receive their award at the Bologna Children's Book Fair.  In December 2009, Time Flies won in the “New Publications” category at the CJ Picture Book Festival is Seoul, Korea. Review: A silent book with no words, using photographs of the hands and numbers of different watches to create a world where time stands still, to reconstruct another time, another place, and another perception of what is around us and what we take for granted. As time flies, this book invites us to fly with time and look at things not as we think they are but as we construct them to be, allowing every reader to interpret and tell the story as they see and would write. Every reader becomes a composer of images and a writer of signs. My Work featured in EMERGENCE, a new publication celebrating contemporary Canadian photography12/22/2009 My work was featured in EMERGENCE, a new publication by Gallery 44 that celebrates contemporary Canadian photography. It is an attractive volume with solid essays by Matthew Brower, Liz Park, Gabrielle Moser, Marie Fraser and Katy McCormick. I was selected by Suzy Lake. Suzy Lake: "I chose Susana Reisman because of her interest in how we see, counter to assumptions of photographic information. There is a sense of extended duration in her works Camera Lucida and On the Scale of History that allows us to accrue detail towards a subjective experience of her photographs. These works are sequenced to a “panorama” for space or movement, rather than a topical narrative.

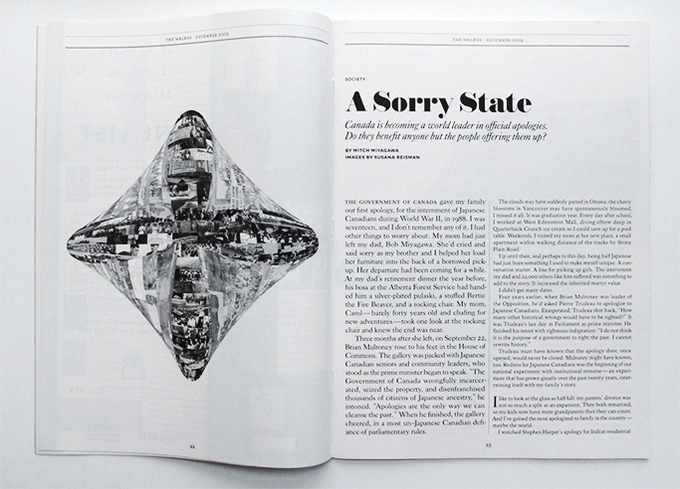

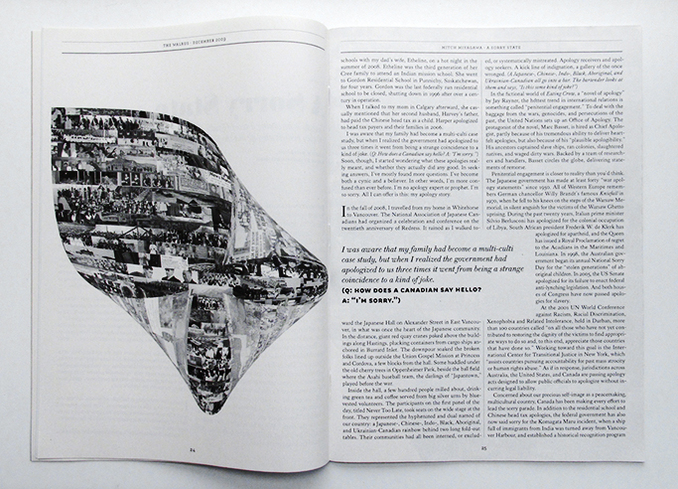

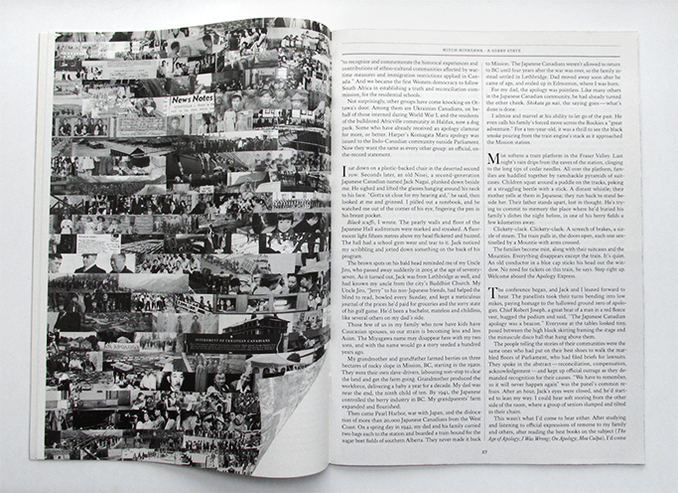

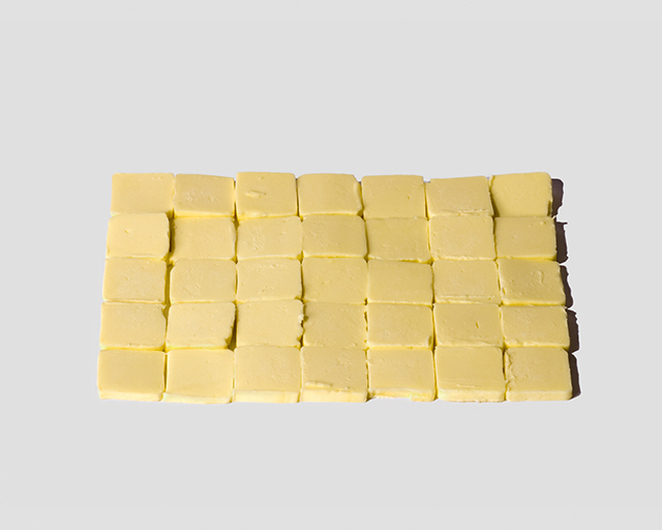

The subject matter in both of these series us a staging or sculptural construction of seminal texts on photography. To photographers, our past moves linearly present. Thought becomes material. And this emphasis on materiality brings poetry to “about photography.” Form and content marry."  My artwork is featured in the December 2009 issue of Walrus Magazine. It accompanies the cover story by Mitch Miyagawa. Marusya Bociurkiw writes about my “butter series” as part of Circuit Gallery's “Critics Choice.” Butter, Art, and Affect by Marusya Bociurkiw “Butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth.” That was what I heard a rather proper United Church lady said about a young rebellious boy. I was a university student at the time, hired by the church to supervise the weekday feeding of breakfast to low-income children, in an otherwise well-heeled suburb. I had no idea what the lady’s comment meant, but the way she said it implied wrongful doing, or at least the potential for it. Sure enough, a few weeks later, the troubled boy pulled a knife on me. It was a dull kitchen knife; his hand shook as he held it. I gently pulled the bread knife out of his hand and then fed him some oatmeal. He went from angry aggression to meekness in a matter of minutes. Affect, fluid, irrational and changeable, can be like that (I never told the church lady about the incident). Years later, I looked up the phrase. It’s meant to describe someone so cold they don’t even have the warmth to melt butter. I see now why I was confused. The boy was warm, hot, even: anger and confusion seethed through his veins. And butter, it seems to me, is almost always cold, shining with refrigerated gloss. But it can melt, too, just like the boy. When I look at the series of photographs of sculptures featuring butter by Susana Reisman, I have a similar sense of contrasting temperatures. The careful arrangement of sticks and slices of butter references the work of artists like Carl Andre whose work, iconic of minimalism, attempted to remove all trace of affect from the process of making or viewing a work of art. No expression, no metaphor, no allusion. At a time, the 1960′s,when consumption and affect were becoming inextricably linked via advertising, stripping art to its bare elements could also be seen as a statement against capitalism in general and the art market specifically. But affect is also of the body and those minimalist works did and do evoke feeling. Affect occurs in contact zones, between and among art works and bodies. A gallery, even an online one, is a contact zone, mediated by various presences. You can look at a work of art and feel many things: anger at not understanding what you think is meant to be understood; pleasure in regarding, perhaps even touching, smooth polished surfaces or rough distressed edges. You might feel pride in your own ability to appreciate a difficult work and that might sit against some secret, sticky shame – the bad reproductions hanging on your office wall, perhaps, or the ways in which your day job erodes your creative soul. Butter may be cold initially, but there is a certain luxury to it, a sense of excess. I make my pie pastry only with butter – I use Joy of Cooking’s pâte brisée recipe, ignoring the call for 1/4 cup of shortening. Julia Child, that extreme butter enthusiast, provides us, in her infamous cookbook, with a multitude of uses for butter, from all manner of sauce to garnish (fill a pastry bag with butter and squeeze it out in fancy designs to adorn an appetizer plate). As I know from the experience of consuming my mother’s baking, there may be shame in consuming so much butter, but shame intersects with interest, a connection to other bodies and thus to the world. Eating mama’s torte links me to history, which is in part a history of domestic artistry, and a chain of affects that have shaped me both as a foodie and as an artist. Reisman’s homage to Carl Andre, The Real Thing, is, like butter, temporary, fleeting, almost casual. It will melt. The use of domestic elements in art can be traced back through the history of painting but was foregrounded in both an ironic and political manner by the second wave feminist art movement. In this series, butter was pulled out of the fridge, mused upon, played with, in repetitive gestures evocative of domestic labour. I wonder: was the butter used up later in a sauce or a cake? Did it get slathered onto a thick slice of bread? I think about Su Richardson’s crocheted “Burnt Breakfast,” Martha Rosler’s “Semiotics of the Kitchen.” Marina Abramovic eating an entire onion, weeping. Regret, anger, and a simulated sorrow. I don’t know what I feel when I look at the butter series. I hear my mother’s voice, something about wastefulness. I hear the happy sound of butter sizzling in a pan. I feel pleasure at the domestic familiarity of the work and then I’m afraid that the work will not fulfill my desire, an unnamable, overarching hunger I always feel when I engage with art. Desire that can never really be satisfied; a work of art that is careful not to do so. Like my young charge from years ago: sometimes, I just don’t know what to feel. It’s good when a work of art can do that, engaging you in a slippery circuit of affects, constantly moving and transforming." Marusya Bociurkiw is a media artist, writer, and assistant professor of media theory in the School of Radio and Television Arts at Ryerson University. Her videos and films have screened around the world. She is the author of four literary books, including, most recently, a food memoir, Comfort Food for Breakups: The Memoir of a Hungry Girl. Her monograph, Feeling Canadian: Nationalism and Affect on Canadian Television, is forthcoming in 2010 from Wilfred Laurier Press.

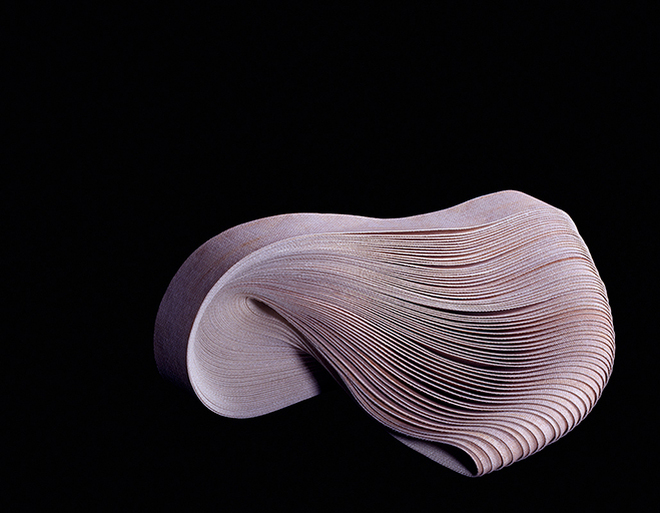

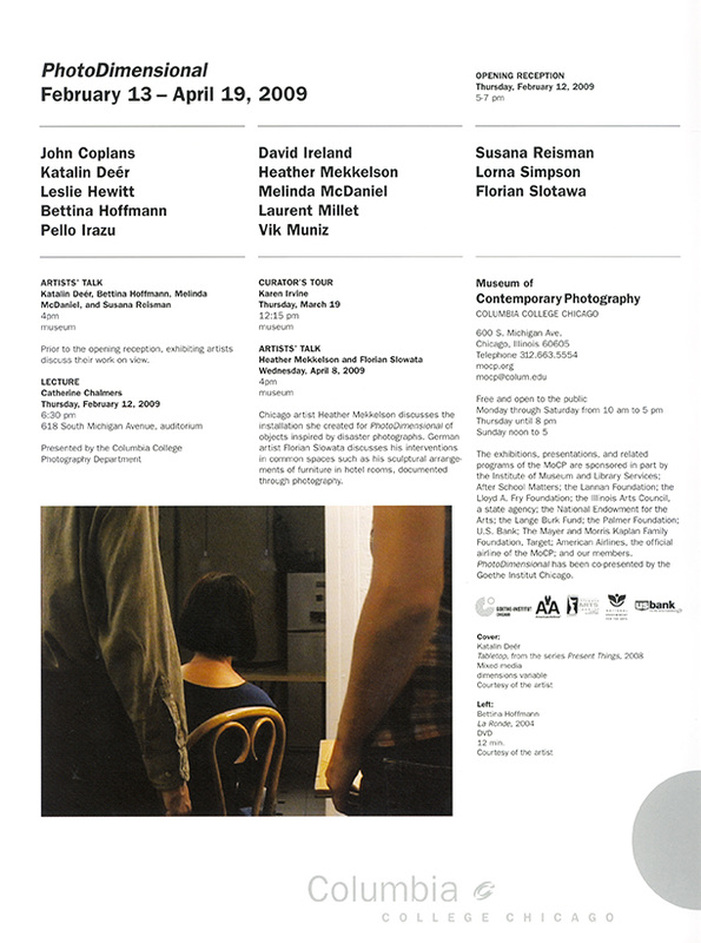

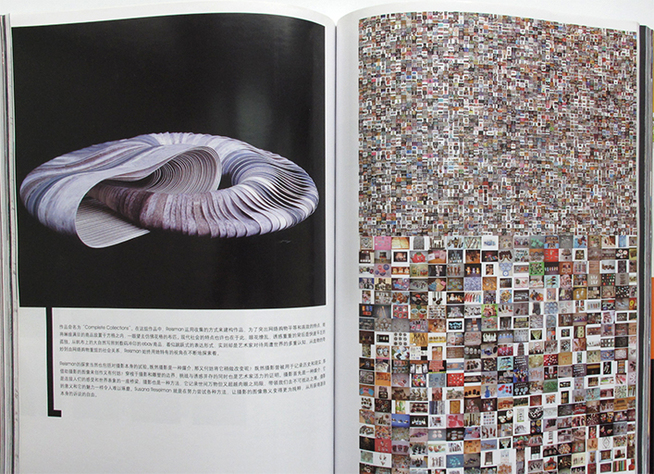

My Photosculpture work was selected for inclusion in the group show “PhotoDimensional” at the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) in Chicago, curated by Karen Irvine. Artists in PhotoDimensional: John Coplans, Heather Mekkelson, Katalin Deér, Laurent Millet, Leslie Hewitt, Vik Muniz, Bettina Hoffman, Susana Reisman, Pello Irazu, Lorna Simpson, David Ireland, Florian Slotowa, Melinda McDaniel. The exhibition runs from February 13 – April 19, 2009  Excerpt from Karen Irvine’s curatorial essay: Found in Translation “It would seem that photography has recorded everything. Space, however, has avoided its cyclopean evil eye.” —Robert Morris, “The Present Tense of Space,” 1978 As Robert Morris, a sculptor, observed, something is inevitably lost when a three-dimensional sculpture is translated into a two-dimensional photograph. The experience of sharing a space with an object (and being able to move around it), and the experience of seeing that object represented and embedded in another object—a flat photographic print—are very different. But do we always experience the photographic image as absolutely flat? Isn’t it the tension between the flatness and the illusion of space in photography—its fidelity to the real—the very thing that makes it compelling, possibly troubling? Photography clearly allows us to imagine space. So is there a strict distinction between phenomenological space and imagined space, and how unambiguous, or understandable for that matter, is the difference between the two experiences? The relationship between photography and sculpture, and the effects that are found in translation between the two mediums, have been of interest to artists since photography was invented. Some of the first photographs featured sculptural objects: both Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot recorded marble statues and plaster casts in the late 1830s and early 40s. An early attempt to overcome the limitations of photography, specifically its inability to translate three dimensions, was the invention of the stereoscope in 1849. Using a special viewing device that rendered two photographs taken of the same subject from slightly different angles, the viewer experienced one image as having lifelike depth and volume. In the early twentieth century sculptural forms fascinated photographers such as Edward Weston, who took pictures of vegetables and shells, Edward Steichen who photographed Auguste Rodin and his sculptures, and Man Ray, who studied the female form. One recent example of artists documenting what they considered to be “found” sculptures is Bernd and Hilla Becher’s first book, Anonymous Sculptures: A Typology of Technical Buildings, published in 1970, which presents multiple pictures of lime kilns, cooling towers, and silos as elegant structures without any overt pictorial embellishment or romanticism. In the 1980s Robert Mapplethorpe used dramatic lighting and cropping to make nude photographic studies that refer to photographs of sculptures from art history. His two-dimensional translations of his models arguably increase the feeling of the body’s weight, mass, and permanence beyond what would be experienced by seeing it in the flesh. And of course there are artists who use photography to more practical ends to document their sculptures, especially if their creations are ephemeral or remote, such as Andy Goldsworthy’s interventions in nature and Robert Smithson’s land art. Similar to performance art, photographs allow this type of work to be documented and disseminated. These documents raise the question of the privileging of experience, and circle back to Morris’s concerns about documents always lacking some aspect of the firsthand experience. PhotoDimensional is an exhibition of works by contemporary artists who investigate the relationship between sculpture and photography, between two and three dimensions, and explore perceptual issues intrinsic to those relationships. Their works resist the notion that the world simply gets folded into the two-dimensional surface of the photograph. As a result, their works are almost always layered, with subjects translated in ways that invite us to imagine passing from the experience of one dimension to another, and sometimes back again. Thus, perceiving their works provokes feelings of unsettledness, a wavering between seeing and knowing in our minds, a tension that becomes an engaging condition of their artwork. [...] Excerpt from Karen Irvine’s curatorial essay: Found in Translation “It would seem that photography has recorded everything. Space, however, has avoided its cyclopean evil eye.” —Robert Morris, “The Present Tense of Space,” 1978 As Robert Morris, a sculptor, observed, something is inevitably lost when a three-dimensional sculpture is translated into a two-dimensional photograph. The experience of sharing a space with an object (and being able to move around it), and the experience of seeing that object represented and embedded in another object—a flat photographic print—are very different. But do we always experience the photographic image as absolutely flat? Isn’t it the tension between the flatness and the illusion of space in photography—its fidelity to the real—the very thing that makes it compelling, possibly troubling? Photography clearly allows us to imagine space. So is there a strict distinction between phenomenological space and imagined space, and how unambiguous, or understandable for that matter, is the difference between the two experiences? The relationship between photography and sculpture, and the effects that are found in translation between the two mediums, have been of interest to artists since photography was invented. Some of the first photographs featured sculptural objects: both Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot recorded marble statues and plaster casts in the late 1830s and early 40s. An early attempt to overcome the limitations of photography, specifically its inability to translate three dimensions, was the invention of the stereoscope in 1849. Using a special viewing device that rendered two photographs taken of the same subject from slightly different angles, the viewer experienced one image as having lifelike depth and volume. In the early twentieth century sculptural forms fascinated photographers such as Edward Weston, who took pictures of vegetables and shells, Edward Steichen who photographed Auguste Rodin and his sculptures, and Man Ray, who studied the female form. One recent example of artists documenting what they considered to be “found” sculptures is Bernd and Hilla Becher’s first book, Anonymous Sculptures: A Typology of Technical Buildings, published in 1970, which presents multiple pictures of lime kilns, cooling towers, and silos as elegant structures without any overt pictorial embellishment or romanticism. In the 1980s Robert Mapplethorpe used dramatic lighting and cropping to make nude photographic studies that refer to photographs of sculptures from art history. His two-dimensional translations of his models arguably increase the feeling of the body’s weight, mass, and permanence beyond what would be experienced by seeing it in the flesh. And of course there are artists who use photography to more practical ends to document their sculptures, especially if their creations are ephemeral or remote, such as Andy Goldsworthy’s interventions in nature and Robert Smithson’s land art. Similar to performance art, photographs allow this type of work to be documented and disseminated. These documents raise the question of the privileging of experience, and circle back to Morris’s concerns about documents always lacking some aspect of the firsthand experience. PhotoDimensional is an exhibition of works by contemporary artists who investigate the relationship between sculpture and photography, between two and three dimensions, and explore perceptual issues intrinsic to those relationships. Their works resist the notion that the world simply gets folded into the two-dimensional surface of the photograph. As a result, their works are almost always layered, with subjects translated in ways that invite us to imagine passing from the experience of one dimension to another, and sometimes back again. Thus, perceiving their works provokes feelings of unsettledness, a wavering between seeing and knowing in our minds, a tension that becomes an engaging condition of their artwork. [...] Read the entire essay by Karen Irvine as it originally appeared on the MoCP website.

|